Ensuring that Anglesey remains a Welsh language stronghold following decades of decline has been earmarked as a key aim of decision makers, with real fears it could become a minority tongue unless action is taken.

While it was once rare to hear English spoken at all in vast swathes of the island – with over 80% noted as fluent Welsh speakers in 1951 – community shifts, an economic slowdown and an influx from the east contributed to that figure slumping to just 57.2% by 2011.

But facing the daunting prospect of Welsh becoming a minority language on Môn for the first time in recorded history, efforts are now underway to reverse the situation by way of encouragement both within and outside of the council’s structure.

When the current language strategy was set up in 2016, factors blamed on this decades long decline included a weak economy and unstable local housing market resulting in “real challenges” in retaining young people and families on the island.

More recently heightened concerns include a rapid rise in the number of second homes being snapped up – particularly in tourist-attracting coastal communities where the language already tends to be heard less often.

But determined to ensure that yr iaith Gymraeg remains a part of daily life within communities from Burwen to Bodorgan and Penrhos to Penmon, council chiefs have targeted an increase of fluent islanders by at least three percent by the next census in March 2021.

This is despite several setbacks for well-paid job creation projects including Wylfa Newydd, with the current pandemic only likely to exacerbate north Wales’ economic woes.

Working hand in hand with nationwide efforts to bolster the numbers of Welsh speakers to one million by the year 2050, the council’s Welsh language portfolio holder outlined the ambition of at least matching the 60.1% figure that was recorded in the 2001 nationwide survey.

“I feel there’s been a shift over recent years and it’s quite clear from general discussions and social media, and even public demonstrations over recent weeks, that people are genuinely getting worried about the situation and what they’re seeing in their own communities,” Cllr Ieuan Williams told the Local Democracy Reporting Service.

“That said, it’s important that we do whatever we can now and bring people with us on this journey.

“We feel that a joint approach, working with lots of other public organisations and through the schools and colleges is the way to encourage the not so confident speakers.

“To bring people with us we have to ensure that the opportunities to learn and grow in confidence in speaking Welsh are there and that people are aware of the benefits of bilingualism and how important Welsh is as part of our national culture.

“Thankfully there are plenty of people out there who are passionate about the language and want to ensure it continues as a community language for decades to come.”

One of only two counties where Welsh remains a majority spoken language – behind Gwynedd (65.4%) – Anglesey’s efforts are concentrated on three main aims, namely children and families, the council’s workforce and services, and usage within the community.

A multi-agency strategic forum has been sitting since 2016 to try and increase opportunities for people to use the language, with a report this week confirming that efforts to introduce Welsh as the main language of administration within the council is progressing well.

This work is being done on a department by department basis, but would continue to maintain a bilingual presence when dealing with the general public, with a recent survey finding that around 80% of staff were almost or wholly fluent.

The first departments to be earmarked – namely housing, leisure and public protection – seeing staff training to boost their ability and confidence in using the language both internally and with the public.

Cllr Williams added: “Following the break-up of the former Gwynedd, Anglesey wasn’t as forceful in adapting a formal policy making Welsh the administrative language, unlike the current Gwynedd.

“There (Gwynedd) it seems to have been a success and has helped protect the language in the public sector, whereas here we have an overwhelmingly Welsh-speaking workforce where Welsh is used as the language of communication but only partly for formal written communication.

“As a result the confidence hasn’t always been there when writing formal documents or even emails, so we’ve been working on this and are already seeing some positive results and the response from staff has been good.”

The overall strategy, when implemented in 2016, acknowledged factors which had contributed to a decline in the percentage of Welsh speakers on Anglesey, including:

Demography and the impact of immigration, a reduction in the numbers of homes for the elderly speaking Welsh and the outward migration of young people to pursue education and careers.

A weak economy and the over-reliance on the public sector and some specific industries along with the unstable housing market

A reduction of language transfer within the family

The challenge of demographic change was made clear in the findings of the last two censuses, with the percentage of islanders born outside Wales increasing from 32.4% to 33.6% between 2001 and 2011.

In 2011, of those on Anglesey born in Wales, 78.2% could speak Welsh compared with 80.8% in 2001, but of those born outside Wales only 17.6% could speak Welsh in 2011 compared to 18.7% in 2001.

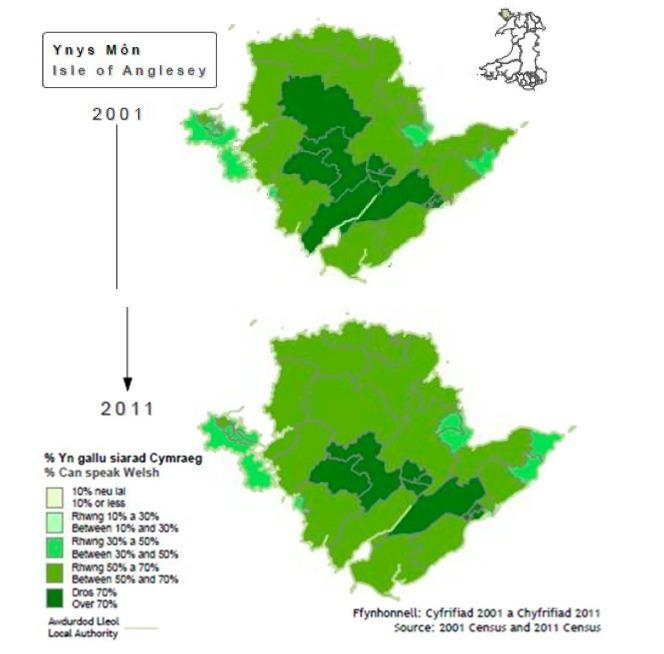

But with the number of communities where over 70% could speak Welsh also decreasing over the past decades, this in itself has been described as threatening Welsh as a living, community language.

This is due to 70% being accepted as a “tipping point,” with experts in the field of sociolinguistics believing that retreating accelerates as the percentage of speakers falls below this level.

“The decline is then sudden and occurs for many different reasons – mainly due to an increase in mixed language marriages, a reduction in the frequency of use, lack of confidence, the increasing spread of English into Welsh social domains and a perception of the worthlessness of the language in a world that is gradually becoming increasingly uniform and Anglo-American,” noted the report.

“It could be argued that if the decline were to continue, it could threaten the existence of the Welsh language as it would no longer have the natural environment in which it was spoken in a variety of social situations.”

In 2001, there were 10 wards in Anglesey where over 70% of their population spoke Welsh, but by 2011 the number had dropped to eight with only the Llangefni communities of Cyngar, Tudur and Cefni recording figures of over 80%.

The lowest proportion of Welsh speakers in 2011 was found in Rhosneigr, with only 36% speaking Welsh, and 38.1% in Trearddur Bay.

But there has been more positive moves in the form of education with an increase of 16% of pupils educated and assessed through the medium of Welsh in the Foundation Phase (aged 4-7) since 2015 (87.5%), with 86.7% doing so in Key Stage 2 (7-11).

Meanwhile, 65% of pupils are now studying Welsh as a first language at GCSE level, with the emphasis now on developing the secondary sector.

Wider measures have seen the Urdd reach its highest ever membership figure of over 3,000 in 2017, the establishment of a club to encourage the use of Welsh at the mainly English-medium Ysgol Uwchradd Caergybi.

Menter Iaith Môn, the Anglesey Language Enterprise, has also been active in holding workshops to encourage families to use Welsh.

Having received backing from the Welsh Language Commissioner as a model of best practice, Cllr Williams concluded with his wish that other local authorities should follow Anglesey’s lead while also encouraging as many non-Welsh speakers as possible to learn the language – which can now even be done online thanks to services such as Duolingo.

But any such efforts come amidst a backdrop of much publicised concerns over the stability and feasibility of the local housing market, with Cllr Williams accepting that coastal communities face their own particular challenges but the authority having too little influence over housing and taxation despite intense lobbying over recent months.

Among those powers is a claimed lack of control over housing and taxation, which recently prompted the council Executive to write to the Welsh Government urging action.

The measures sought include any application to convert a regular dwelling into a second home having to first obtain planning permission – with second homes said to have made up 36% of the island’s property sales last year.

While a 35% council tax premium is already slapped on such holiday homes, the authority is also believed to be losing out on around £1m a year in lost income due to several second home owners using a tax “loophole” to switch from domestic to business rates – often ending up paying no rates at all.

The letter, written by the council leader, goes on to call for any property that transferring from the Council Tax to the Business Rates register to not be eligible to receive assistance through the Small Business Rate Relief scheme and for the Valuation Office to more regularly audit properties that are designated as self catering accommodation to ensure that they continue to meet the criteria.

“The fact that properties on Anglesey are being purchased as investment properties by non-Anglesey residents drives up the prices of houses when they come on the market, which makes them less affordable to Anglesey residents who are looking to purchase their own home,” wrote Cllr Medi.

But the issue has also gained traction outside of the chamber, with a recent protest in Llangefni also calling for urgent legislation to clamp down on second and holiday homes.

Attracting around 50 people, campaigners claimed that villages and towns across the island were “changing before their very eyes”.

While 2011 census figures showed that 43% of homes in Rhosneigr and 34% in Trearddur Bay were empty for most of the year, they claimed that the ratio is now as high as 70% in some villages.

The island’s MS, Rhun ap Iorwerth, said at the rally that the situation is now an “emergency” in many communities.

“Something has to be done, there are steps that can be taken in terms of planning and taxation policy as the way things are going our young people are being priced out,” he said.

“We know the percentage of second homes is growing and has raised staggering figures in some areas, look at somewhere like Moelfre where up to three quarters of houses are now said to be second homes.

“How can being largely dead over the winter not impact on the character of a village?”

The Welsh Government has been approached to respond but speaking in the Senedd recently, Welsh Language Minister Eluned Morgan conceded it was a “really complex issue” but that the Government was determined to make it possible for people who are brought up in an area to be able to stay there.

She added that Wales was the only UK nation where local authorities can charge up to a 100% premium on the standard rate of council tax on second homes.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel